Despite the fact that Bizet’s Carmen is one of the most performed operas sitting along side Puccini’s La Bohème, Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, and Verdi’s La Traviata, the original reception of Carmen was in many ways a failure. Perhaps at the time of the premiere of Carmen (1875) much of the public was alienated by the true sense of shocking realism of the story, where a new type of operatic heroine was introduced. Typical audiences who expected stereotypes and happy endings were confronted by a promiscuous gypsy girl whose intoxicating dramatic story leads irresistibly to the climax of her being murdered.

Bizet’s music also portrays a simple directness capturing Carmen’s fatalism and courage as well as Don José’s gradual degeneration. This musical truthfulness seemed to also offend the opera’s first audiences in Paris.

Set in the exotic Spanish city of Seville at the beginning of the nineteenth century and based on the novel by Prosper Mérimée, Carmen was adapted for the stage by French librettists Ludovic Halévy and Henri Meilhac. At the center of the story is Carmen’s seduction of a young corporal, Don José, who tosses aside the love of the more respectable Micaëla in favor of the alluring Carmen. Carmen eventually abandons her love for Don José and turns her attention to the dashing bullfighter Escamillo. Carmen’s scornful taunts eventually bring Don José to a jealous rage, and he stabs her to death.

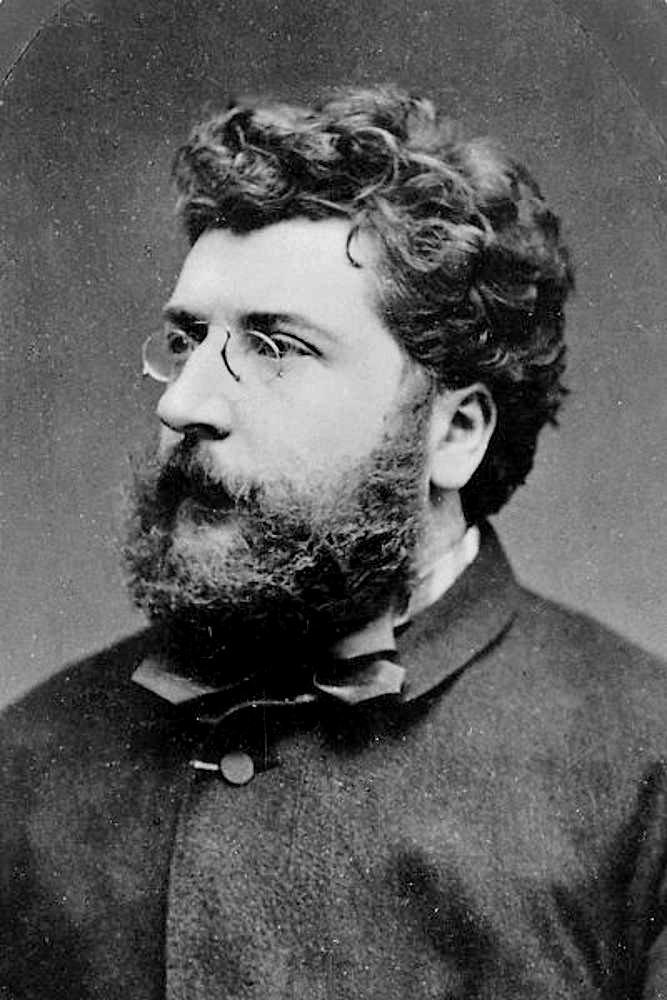

Born to a very musical family, Bizet entered the Paris Conservatory at the young age of nine and later won the coveted compositional award of the Grand Prix de Rome. Most of Bizet’s compositional thoughts were aimed at imitating his mentor, Charles Gounod; however, Bizet’s style proved to be far more advanced.

Much of Bizet’s career proved to be a series of a few mediocre successes coupled with several failures. His musical gifts and extraordinary insights seemed to almost prevent him from completing many projects. In addition to Carmen, Bizet composed a symphony, twelve works for piano duet titled Jeux d’enfants, a one-act opera (Djamileh), incidental music to the play L’Arlesienne, and the operas The Fair Maid of Perth, The Pearl Fishers, and several other lesser known operas.

With Carmen, Bizet makes effective use of Spanish rhythms and melodic turns, especially with the heroine herself. Memorable moments are known to audiences who have never seen Carmen, such as the “Habañera” which exotically captures the seductive Carmen as she sings about the nature of love and her creed of freedom – living, loving, and dying as she chooses, while the soldiers become hypnotized by the sexy, almost smoky vocal range of Carmen’s first appearance.

From the softer and gentler movements for soprano Micaëla to the brassier, machismo music associated with Escamillo and the bullfight, Bizet constantly evokes the eroticism of Spain and creates a masterpiece of local color and warmth. The brilliance of Carmen not only rests with Bizet’s score, but also with the concept and dramatic elements of how the composer and librettists presented the work. Carmen was extremely innovative in its drama: no longer was French opera confined to one-dimensional comic characters and in many ways the two principal characters, Carmen and José, are some of the most profound in all of operative literature. Don José transforms from an exemplary soldier and faithful lover to almost an obsessed lunatic. In many ways Carmen symbolizes not only the exotic land of Spain, but also represents a toreador luring the bulls to their own demise. Later she transforms into the bull herself and is in a sense sacrificed exactly when the bull is being killed.

Musically, the three highlights between Carmen and José are quite symbolic. The three duets suggest a development and destruction of their relationship: seduction, conflict, and finally, resolution, as Carmen’s death is not only predicted throughout the opera but it is necessary for her own completion. Contrary to most love duets, Carmen and José’s voices never truly become one, in fact, they almost never sing together.

While not as dramatically developed as Carmen and José, Micaëla, Escamillo, and Zuñiga (José’s superior officer, who also attempts to pursue Carmen) also seem to represent important dramatic structures of the opera. Micaëla represents José’s past, his mother, and even his small village, whereas, Zuñiga represents Carmen’s past, José her present, and Escamillo her future. Musically, Micaëla’s duet with José and her aria almost seem right out of a Gounod opera (Bizet’s teacher) where Escamillo’s toreador solo comes from the opera buffa (comic opera) tradition. Bizet knew that the toreador song would be popular, but he personally despised it, saying “They want their trash, and they will get it.”

While the score is obviously French, Bizet elegantly works elements of Spanish music into Carmen, such as a gypsy song, some flamenco dancing, and the famous “Habañera” (of which Bizet made over ten revisions). Giving into Wagner’s influence over nineteenth century operas, Bizet makes the orchestra as important as the singers (which several French critics disliked) and uses Wagner’s concept of leitmotif where certain musical themes are associated with specific characters and ideas. Carmen and her death are represented immediately after the overture to the opera with a slow, mysterious, and haunting melody that appears throughout the four acts. In addition to this fate motif, Carmen’s influence over José is captured by a beautifully tragic theme that also is used frequently.

The premiere production was indeed a risky venture for the venerable Opéra-Comique in 1875. In spite of his training at one of the most respected conservatories and winning the most coveted prize for composition in all of Europe, Bizet was not a well-established composer. The Opéra-Comique in Paris had become a venue that attracted families and a conservative crowd accustomed to sentimentality, moral plots, happy endings, and elements of the supernatural and exotic. In many ways Carmen met the expectations of the exotic, but the realism, amoral characters, tragic ending, and absence of fantasy put off much of the audience and critics. Even the elements of the exotic Seville and lead character, who exemplified a bold, reckless, and dangerous female, were not appealing. When the subject of Carmen was proposed to the theatre one of the directors of the company resigned in protest. A friend of one of the librettists commented “I won’t mince words. Carmen is a flop, a disaster! It will never play more than twenty times.”

Carmen was not well-received in Paris nor during Bizet’s lifetime; however, when the opera premiered in Vienna, it quickly became part of standard repertoire. Bizet’s score not only has remained one of the most popular operas, but a number of other composers have used themes from Bizet’s score as the basis for their own works: Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy for violin and orchestra, film composer Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasie, and pianist Vladimir Horowitz’s Variations on a theme from Carmen for solo piano.

In this last work of Bizet’s, Carmen became the musical representation that linked Bizet as the true bridge between Berlioz and Debussy. His death at the young age of 36 (just after the thirtieth performance of Carmen) is today believed to be the greatest single blow to French music in the nineteenth century. In many ways it seems a necessity and less of a tragedy for the femme fatale in the opera to die, as the real tragedy and conclusion of the opera is perhaps Bizet’s death so suddenly and so young, and never able to see the success of his greatest work.