Saturday, 23 October 2021

7:30 p.m. MST

Helena Civic Center

Watch live on YouTube.

Saturday, 23 October 2021

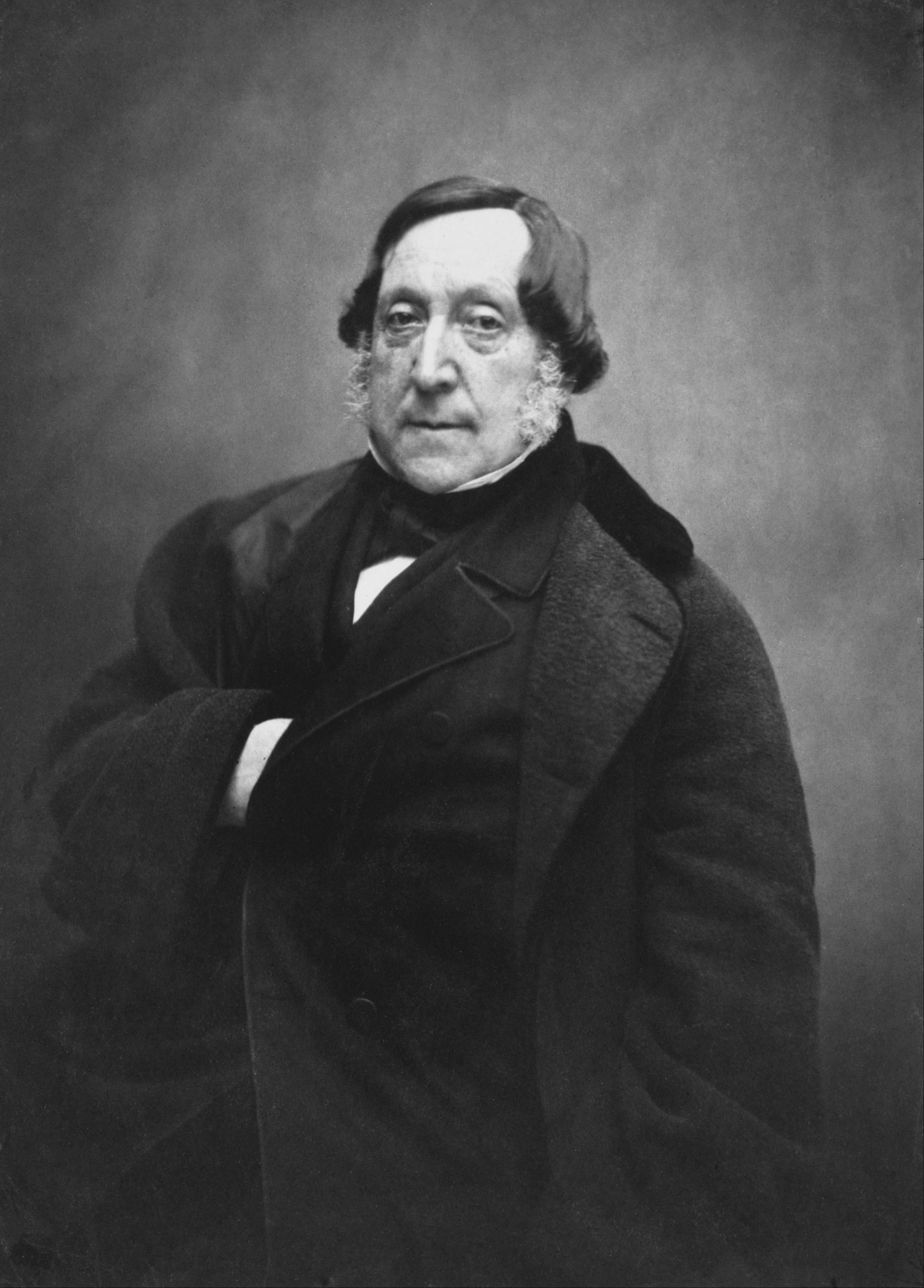

A concert of healing to remember those lost during the pandemic – three miniatures of Mahler allow us to reflect. Legendary Italian composer Gioachino Rossini brings his flair for operatic drama, passion, love, and loss to the setting of Stabat Mater – a recounting of the Virgin Mary’s devastation over the death of her son.

Reflect, remember, and heal with us.

Enter the names of loved ones you have lost and would like to be remembered.

Cheryl Leptich

Ardelle Thronson

Jack Hamlin

Merry Lunde

Merton Paul Zuelke

Margarette Ann "Mike" Archibald

Marcie Bugni

Curtin Stinson

Brian Humle

Sonny Stiger

Chief Earl Old Person

John Prine

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Debbie Zuidema

Kay Francis Cohen

John A. Teberg

Sandra Brockbank

Cory Casagrande

Dr. & Mrs. William Ballinger

Barbara Kenny

Robert Cummins

Bruce Duenkler

Echolyn Travis

Maggie Long

Tim Reardon

Susan Hamilton

Henry Van Wormer

Wayne Peterson

Patsy Spear

Rodney Capistran

Ella Auch Shields

Tony Harrah

John P. Shaw

Russ Cargo

Heather Barnes

Murphy Fox

Joan Duncan

Byron Roberts

Irene Roberts

Ed Noonan

Harry Greisser

Josephine Therriault

Irene Kolbash

Russel Cargo

Currently in his nineteenth season as Music Director of the Helena Symphony Orchestra & Chorale, Maestro Allan R. Scott is recognized as one of the most dynamic figures in symphonic music and opera today. He is widely noted for his outstanding musicianship, versatility, and ability to elicit top-notch performances from musicians. SYMPHONY Magazine praised Maestro Scott for his “large orchestra view,” noting that “under Scott’s leadership the quality of the orchestra’s playing has skyrocketed.”

About the Guest Artists

Keeping You Safe in the Concert Hall

Due to the recent increase in COVID-19 cases and new variants emerging in Lewis and Clark County and the United States, the Helena Symphony will take necessary precautions to keep our musicians, staff, and audience protected. The Helena Symphony will continue to follow CDC guidelines throughout Season 67 and monitor the daily transmission rates within our county. When the transmission rate is high or substantial, audience members will be required to wear a mask while in the concert hall. On concert nights when the transmission is moderate or low, individuals will be encouraged to wear a mask, but are not required to do so.

Each member of the Helena Symphony Orchestra & Chorale will be tested prior to rehearsals and prior to each concert. This will ensure each musician present on stage is negative for COVID-19. The Helena Symphony will continue to work closely with the county health department and the city of Helena throughout the Season to ensure the safety of our musicians, staff, and audience. If you have questions about how the Helena Symphony will be adapting to the evolving COVID-19 situation this Season, please call our office at 406.442.1860.

About the Program – By Allan R. Scott ©

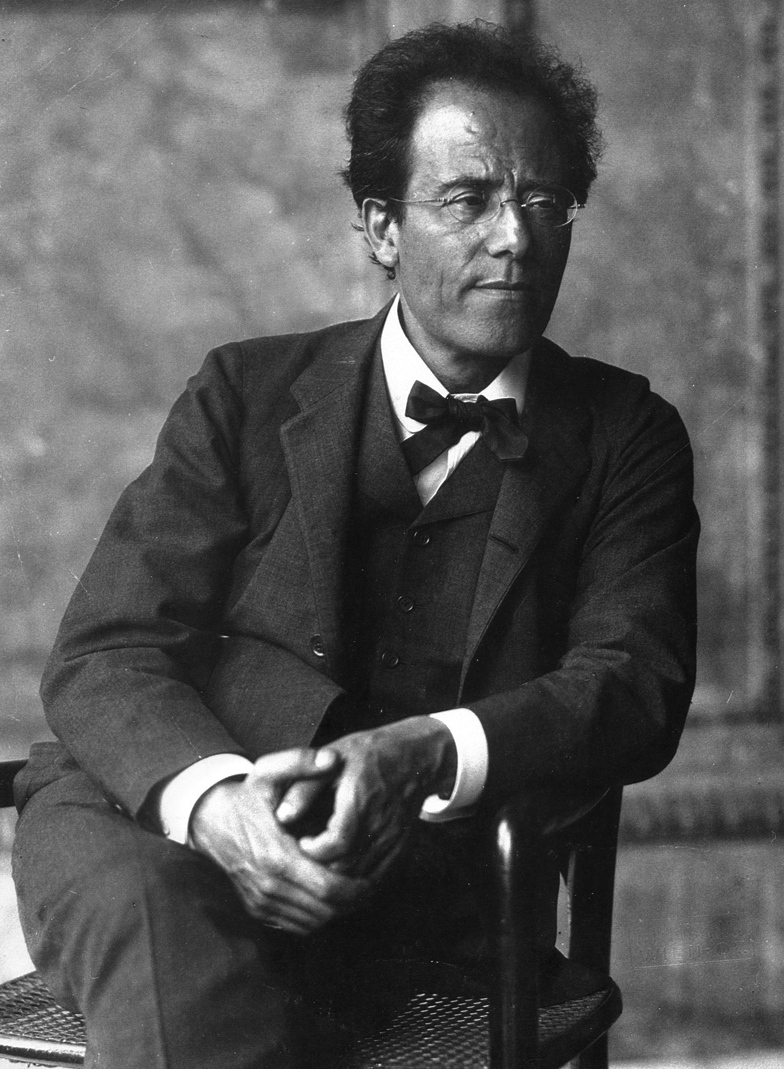

GUSTAV MAHLER

Born: 7 July 1860 in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: 18 May 1911 in Vienna, Austria

Parallel Events / 1884

Sino-French War begins

Grover Cleveland is elected the 22nd U.S. President

The Washington Monument is completed, making it the largest structure in the world at the time

Dow Jones index is created

First Oxford English Dictionary is published

Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is published

Local anesthesia is invented

U.S. President Harry S. Truman and U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt are born

Composer Bedrich Smetana, Alice Roosevelt (wife of Teddy Roosevelt), and Martha Roosevelt (mother of Teddy Roosevelt) die

Blumine (Blossoms)

Mahler’s Blumine is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, trumpet, harp, and divided strings.

Duration: 7 Minutes

Parallel Events / 1901

U.S. President William McKinley is assassinated. Theodore Roosevelt becomes 26th President

British Queen Victoria dies

Bruckner’s Sixth Symphony and Mahler’s Symphony

No. 4 premiere

Composer Giuseppe Verdi and 23rd U.S. President Benjamin Harrison die

Walt Disney, jazz musician Louis Armstrong, comedian Herbert Zeppo Marx, violinist Jascha Heifetz, and actors Gary Cooper and Clark Gable are born

First New Year’s Day Mummers Parade in Philadelphia

Adagietto from Symphony No. 5

Mahler’s Adagietto from his Symphony No. 5 is scored harp and divided strings.

Duration: 10 minutes

Parallel Events / 1896

William McKinley elected 25th U.S. President

Utah becomes 45th U.S. state

Nicholas II crowned Russian Tsar

Henry Ford test-drives first automobile

Charles Dow publishes first edition of Dow-Jones Industrial Average

Tsunami in Japan kills 27,000 people

Puccini’s opera La Bohème premieres

John Philip Sousa composes Stars and Stripes Forever March

“When the Saints Go Marching In” is written

First kiss on film

“What the Wild Flowers Tell Me” from Symphony No. 3

Mahler’s “What the Wild Flowers Tell Me” arranged by Benjamin Britten is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, trombone, glockenspiel, suspended cymbal, triangle, tambourine, rute, harp and divided strings.

Duration: 9 minutes

Parallel Events / 1842

U.S. and Britain settle dispute over Canadian border

U.S. passes first child labor laws

New York Philharmonic gives first performance

London Illustrated News is first published

Mount St. Helen’s erupts in Washington state

Jules Verne writes Around the World in 80 Days

Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd marry

Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony, Verdi’s opera Nabucco, and Glinka’s opera Russlan & Ludmilla premiere

Composers Sir Arthur Sullivan and Jules Massenet, Outlaw Jesse James, and German astronomer Hermann Karl Vogel are born

Paper becomes used for Christmas cards

Sewing machine is patented

GIOACCHINO ROSSINI

Born: Pesaro, Italy, 29 February 1792

Died: Passy, Italy, 13 November 1868

Stabat Mater

Rossini’s Stabat Mater is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, divided strings, mixed chorus, and soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, and baritone solos.

Duration: 62 minutes